From Mithras to Jesus: Exploring the Roots of Christianity by Anyalzying Art - Part 1

Note: This presentation may offend some because of its take on the history of Christianity. I want to make it clear that I am in no way attempting to degrade, insult, or make fun of the faith of others. I find these similarities striking and interesting, and I wanted to present them to you here. You may take away whatever you like from it, but I hope you will enjoy reading this as much as I have enjoyed researching and presenting it. -George

The Son of God was born several thousand years ago on December 25. He was described thusly: He "is spiritual light contending with spiritual darkness, and through his labors the kingdom of darkness shall be lit with heaven's own light; the Eternal will receive all things back into his favor, the world will be redeemed to God. The impure are to be purified, and the evil made good" (Plato, Philo, and Paul, p. 15). He was depicted as an infant on the lap of his mother in art, and one of these depictions can be found in the catacombs of Rome. As an adult, he was a traveling teacher and healer, and he had 12 disciples.

His birth was celebrated yearly on December 25, as was his resurrection, which happened 3 days after his death and entombment. His disciples "formed an organized church, with a developed hierarchy. They possessed the ideas of Mediation, Atonement, and a Savior, who is human and yet divine, and not only the idea, but a doctrine of the future life. They had a Eucharist, and a Baptism, and other curious analogies might be pointed out between their system and the church of Christ" (The Christian Platonists, p. 240).

This story sounds familiar to all of you, I'm sure. However, it's not the story of Jesus that I'm telling. It is the story of Mithras. Franz Cumont wrote The Mysteries of Mithra (Full Readable Version Here) in 1903. According to him, Mithraism came originally from Persia (basically modern-day Iran). It's not completely certain when Mithraism was primarily observed, but some scholars place it in the 1st century AD. Others say it could have started before then but was most popular during the first to fourth centuries A.D.

These similarities were no secret to early Christians, because they had to endure the mocking of their pagan neighbors who couldn't understand why they believed in the story of Jesus which was so much like their stories that the Christians discarded. Pagan philosopher Celsus asked this very question: "Are these distinctive happenings unique to the Christians - and if so, how are they unique? Or are ours to be accounted myths and theirs believed? What reasons do the Christians give for the distinctiveness of their beliefs? In truth there is nothing at all unusual about what the Christians believe, except that they believe it to the exclusion of more comprehensive truths about God"

Tertullian, a church father, wrote "The Devil, whose business it is to pervert the truth, mimicks the exact circumstances of the Divine Sacraments, in the Mysteries of idols. He himself baptises some that is to say, his believers and followers; he promises forgiveness of sins from the Sacred Fount, and thereby initiates them into the religion of Mithras: thus he marks on the forehead his own soldiers: there he celebrates the oblation of bread: he brings in the symbol of the Resurrection, and wins the crown with the sword."

Tertullian and the early Christians, then, were so painfully aware that their beliefs were so similar to those of the Dionysus/Bacchus/Mithras followers that they came up with an explanation - Satan himself created these stories before Jesus was born in order to confuse those who might otherwise become Christians.

Many ancient Christian sites are built on top of pagan sites after the Christian religion took over in those places. Italy is no different, with Rome hosting many Christianized sites. St. Clement's Church, one of the oldest churches in Rome, was built on top of a Mithraeum, or Temple of Mithras. This is an image of ruins taken from the Mithraeum:

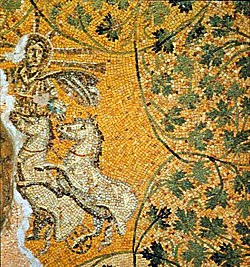

Another such Christianized site is St. Peter's Basilica, the Vatican Church. There are many tombs under the Basilica. These were discovered during a 1939 excavation. Some of the tombs found were non-Christian, and others were Pagan, but one bit of imagery found on one of the Christian tombs is interesting:

This image depicts Jesus, but he is depicted as a sun god or "Sol Invictus," a later form of Mithras.

Mithras is not the only pagan god who shares similarities with Jesus, however. Mithras as savior, son of god, born on December 25 and resurrected 3 days after his death is acting as another representation of the general god-man known to scholars as Osiris-Dionysus. Here you can find a chart comparing many dying and resurrecting god-men with Jesus.

This particular amulet, which supposedly depicts Dionysus/Bacchus, other Roman forms of the god-man, has been claimed a forgery by some, but evidence is inconclusive either way.

Another interesting similarity between pagan and Christian art is the use of pine cones in Dionysus imagery and Christian imagery, particularly in the Vatican and in Catholic dress.

Here, Dionysus carries a pine cone on a staff.

Here, Bacchus carries the pine cone staff.

This is the largest pine cone in the world at the Court of the Pine Cone, Vatican.

The Pope's pine cone staff.

Continue to Part 2